“Prosperity” is one of those things which most people would say is a good thing. Nearly everyone wants “prosperity,” in whatever way they may define it. Yet, how to secure it is a question which creates quite a bit of division, and has indeed birthed many of the almost innumerable ideological conflicts that have plagued the modern world. I believe that much of this has to do with the failure on the part of modern man to adopt a rational definition of “prosperity.”

“Prosperity” is one of those things which most people would say is a good thing. Nearly everyone wants “prosperity,” in whatever way they may define it. Yet, how to secure it is a question which creates quite a bit of division, and has indeed birthed many of the almost innumerable ideological conflicts that have plagued the modern world. I believe that much of this has to do with the failure on the part of modern man to adopt a rational definition of “prosperity.”

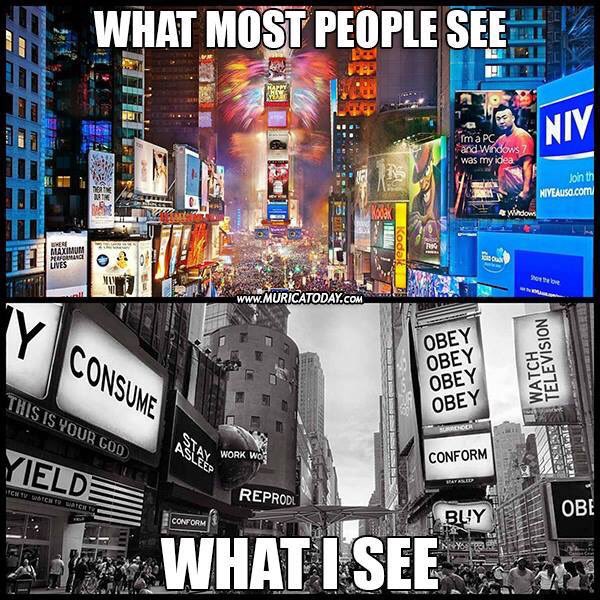

The typical Westerner today, and especially the American, would tend to define “prosperity” in solely economic terms. For them, prosperity is that which leads to economic growth and a greater abundance of superficial expressions of wealth such as access to entertainments or the possession of various status symbols. Prosperity would be measured in increasing GDP, more electronic baubles on the shelf at Best Buy, and an ever-rising stock market index.

However, there is a good argument that can be made that these are not really “prosperity,” in a reasonable and traditional sense of the word. The traditional sense of “prosperity” which has applied for most of human history (once again, we find modernism to be an aberration here, as it is in much else) can best be summed up in the Hebrew (shalowm) and Greek (eirēnē) terms, found in the Scriptures, which the ancients used. Both of these terms transcend the shallow and materialistic sense which modern Western man applies to “prosperity.” Rather, “prosperity” involved a deeper sense of spiritual, moral, and mental peace (indeed, “peace” is a common translation of both of those words). It portended an absence of conflict, not just in the bare sense of not fighting with someone else, but more broadly in leading a stable, well-grounded, balanced life that was suitable for your station in life. To the extent that it involved economics, it did so in the sense of communal abundance grounded in hard work and industry which allowed individuals within a community to lead lives secure from hunger or privation, rather than speculation in commodities or eternal pursuit of wealth and trinkets.

One of the biggest mysteries that plagues the world of neoconservatism is the question of why the end of history – that final triumph of liberal democracy and consumer capitalism – hasn’t occurred yet. All around the world in many different cultures and nations there is a strenuous reaction against these very things. Indeed, even in the western core – Western Europe and the Anglosphere – there is increasing skepticism about these tenets of the Enlightenment.

One of the biggest mysteries that plagues the world of neoconservatism is the question of why the end of history – that final triumph of liberal democracy and consumer capitalism – hasn’t occurred yet. All around the world in many different cultures and nations there is a strenuous reaction against these very things. Indeed, even in the western core – Western Europe and the Anglosphere – there is increasing skepticism about these tenets of the Enlightenment. Of the many pathologies which afflict the modern Western world, one of the most pernicious is the soullessness of Western economic life. The essence of modernity, from an economic point of view, is to work for a repetitive eight hours a day so we can then go home and sit in front of a television for eight more, or else go out to the mall and buy useless junk that we don’t really need. Many in our societies recognise this problem, but feel powerless to do anything about it. We feel locked in, chained to a system which maximises “economic growth” and minimises our humanity. We have no choice but to feed the relentless machine of “progress” by offering ourselves as sacrifices to the great god Mammon.

Of the many pathologies which afflict the modern Western world, one of the most pernicious is the soullessness of Western economic life. The essence of modernity, from an economic point of view, is to work for a repetitive eight hours a day so we can then go home and sit in front of a television for eight more, or else go out to the mall and buy useless junk that we don’t really need. Many in our societies recognise this problem, but feel powerless to do anything about it. We feel locked in, chained to a system which maximises “economic growth” and minimises our humanity. We have no choice but to feed the relentless machine of “progress” by offering ourselves as sacrifices to the great god Mammon. Tradition is one of those terms that’s easy to use, but hard to define. Everyone has their own particular idea of what it suggests, and then, of course, there is the fact that one nation’s general set of traditions may be vastly different from another’s. So in my discussion below, I’m going to implicitly use the term to mean “Western” traditions. When we talk about the traditions of the West, what do we really mean? Are we longing for a turn away from the sort of technological society which we have built since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution? Are we merely talking about a return to simpler days of our nostalgia? What is being said?

Tradition is one of those terms that’s easy to use, but hard to define. Everyone has their own particular idea of what it suggests, and then, of course, there is the fact that one nation’s general set of traditions may be vastly different from another’s. So in my discussion below, I’m going to implicitly use the term to mean “Western” traditions. When we talk about the traditions of the West, what do we really mean? Are we longing for a turn away from the sort of technological society which we have built since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution? Are we merely talking about a return to simpler days of our nostalgia? What is being said?